Reframing Michigan’s Aeronautical Past

Aviation Artifacts Rescued

Aviation Artifacts Rescued

by Sarah Pinkelman

Upgrades to a century-plus old engineering program can result in a chaotic flotsam and jetsam of items over the years, and for the Aerospace department at the University of Michigan, many of them have ended up in the engineering technician space.

Known as a ‘keeper of history’, engineering technician Chris Chartier has an office full of framed photos and objects important to U-M’s aeronautics history, such as alumni among the crews of Apollo 15, the Skylab, and STS-3.

Now, there’s now an obvious blank spot on his wall. “She came and took it,” he says with a laugh, referring to strategic initiatives manager Sheila Waterhouse.

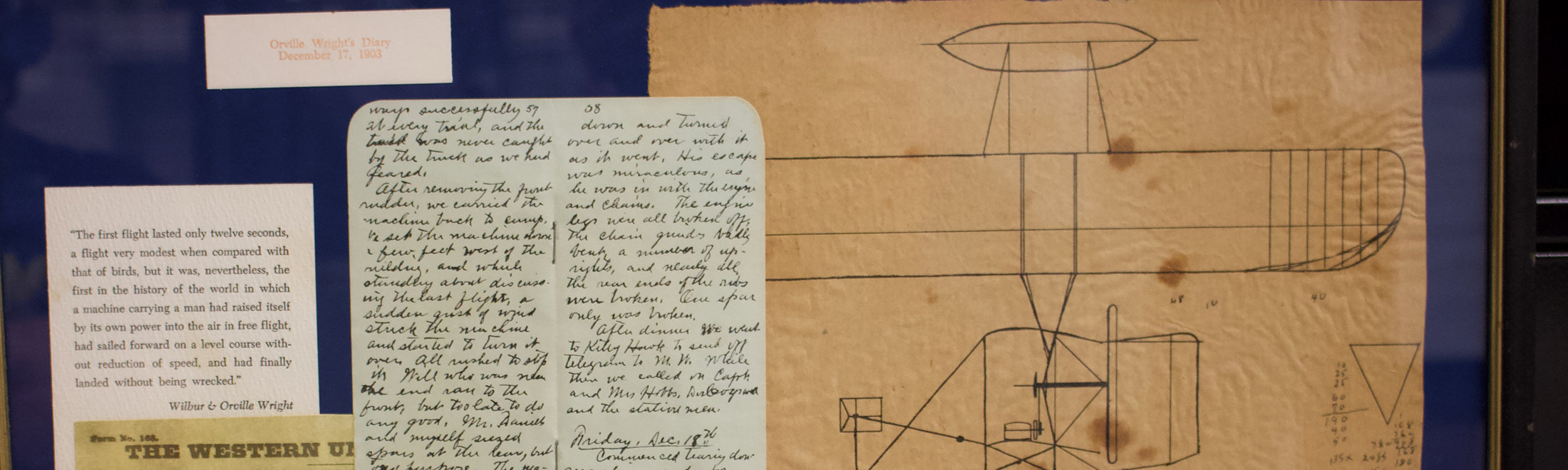

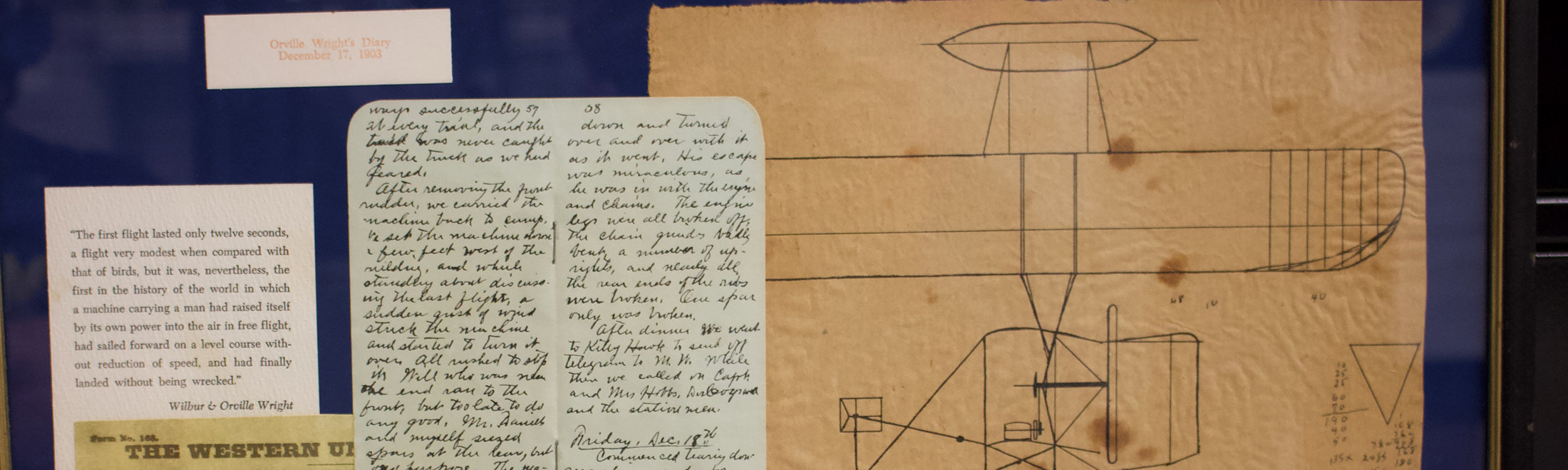

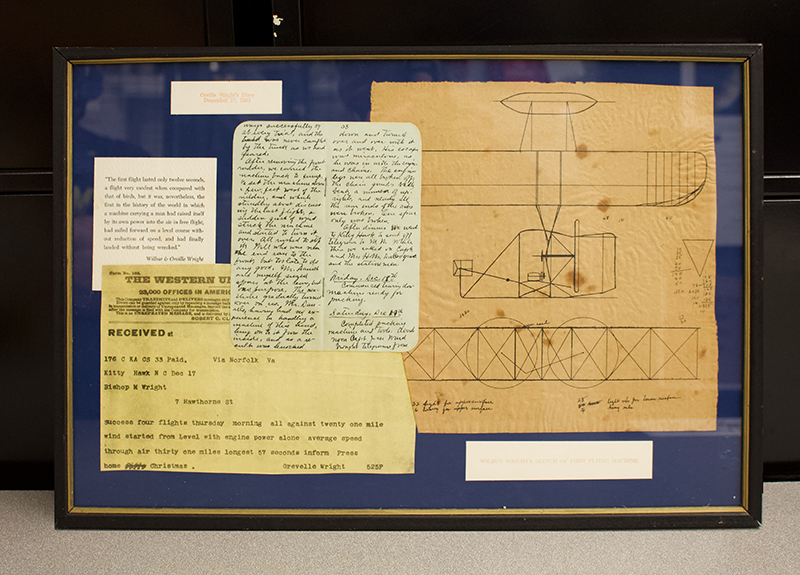

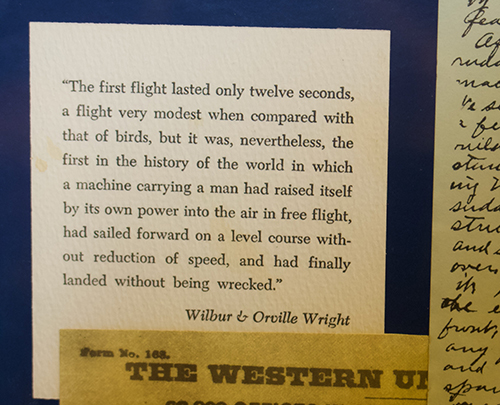

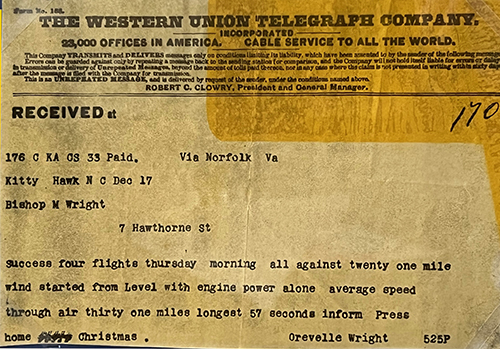

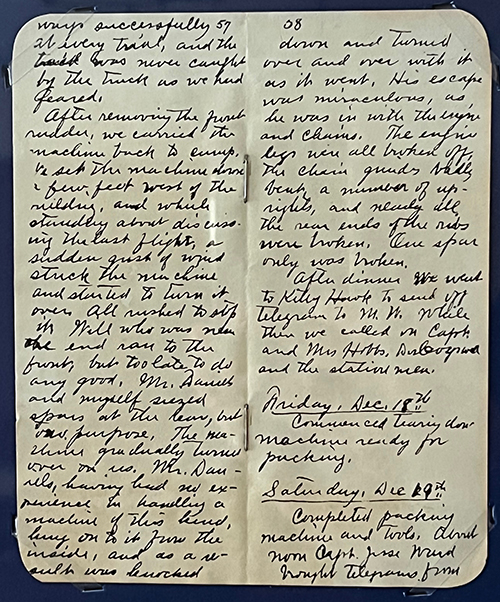

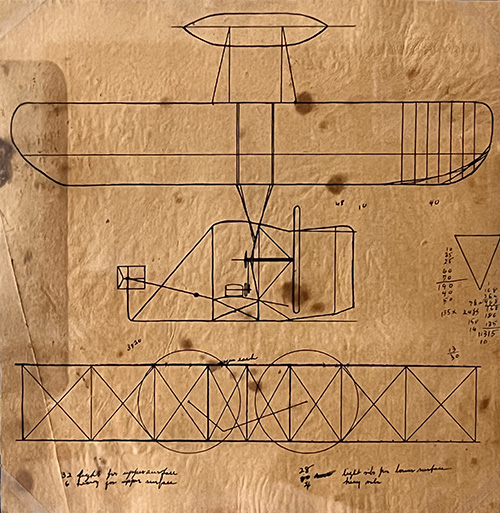

“It came in a box with a bunch of magazines piled on top of it,” says Chartier. When he pulled it out of the box, he couldn’t believe what almost made its way to recycling. It was a framed piece that held three original Wright brothers documents: a page of Orville Wright’s diary from December 17, 1903, an original goldenrod carbon of a telegram of that same date, and a sketch labeled, “Wilbur Wright’s sketch of first flying machine,” with some calculations scribbled on the side. December 17, 1903, “is the day they took the first flight, . . . which was not even the wingspan of an airplane,” says Chartier. The telegram is from Orville to his father and begins, “success four flights Thursday morning all against twenty one mile wind,” and ends, “average speed through air 31 miles longest 57 seconds inform Press home Christmas.” Obviously, Chartier wasn’t about to send this on to recycling.

The frame was falling apart, and while waiting for someone to take care of it, he’d had to put it on the only empty spot he had left, “laying on my floor. And it kept falling over. I was afraid I was going to break the glass.” So he hung it up among the astronaut alumni of Michigan Aerospace Engineering that lined his walls, where it belonged.

Chartier says he’d seen the framed piece when he first started here in 2000; the collection “was hanging in the library on the second floor (which is now grad student cubicles) on a pedestal.” It was moved from place to place and ended up in that box in his office. He recognized it from the library and pulled it out. “I kept asking if anyone was going to do anything with it,” he says, and Waterhouse took over from there.

How the collection came to Michigan Aerospace Engineering is still a mystery, but its presence makes sense: Michigan’s aeronautical program and degree is the first in the country, now the oldest in the world. And while most aeronautics programs might not be in their current state without the Wright brothers, the connection for Michigan’s program has direct links. That’s where Felix Pawlowski and Herbert Sadler come in.

In 1915, students sat in the first course of aeronautical engineering at the University of Michigan. A new teaching assistant named Felix W. Pawlowski delivered the opening lecture for “Theory of Aviation” on February 15. And it was the excitement of Pawlowski witnessing the Wright brothers in France that propelled him to that spot in front of the blackboard. Professor Herbert Sadler, meanwhile, was already running a club at the university that gave interested students real life flying experience.

Sadler had also found academic inspiration from the Wright brothers, but on U.S. soil. In 1964, as part of the celebration of the 50 year anniversary of the program, Professor Robert P. Weeks compiled a “fragmentary, anecdotal history.” He wrote that in order for the program to start, “the keen interest in aviation that had found its stimulus and focus in the Wright Brothers’ pioneer flight in 1903 had to be transformed from a largely avocational, amateur, sporting interest into something professional, scientific and academic.” Pawlowski and Sadler were essential to that transformation.

Herbert Sadler came to the University of Michigan from a post at the University of Glasgow, and took the role of chairman of U-M’s Department of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering. Weeks writes that, “In 1911 after attending the first International Aviation Meeting at Boston where he watched the Wright brothers, Glenn Curtiss, Louis Bleriot, Graham White and others in races and exhibition flights, he returned to Ann Arbor and reorganized the moribund University of Michigan Aero Club.” The club built a wind tunnel and an airplane that, modeled after the Wrights’ bi-plane, was a cross between a kite and a glider.

Wilbur Wright and Sadler corresponded about the plan’s design, with Wright advising him to make sure the students didn’t make it “too light.” Weeks also writes that this first airplane was “succeeded by a model ‘B’ hydroplane built by the Wrights in 1912 and donated in 1915 to the Aero Club . . . During a trial flight from Barton Pond, shortly after the club had gotten it, the hydroplane crashed and was ruined.” That adventurous and daring spirit of that Aero Club combined with the academic constructs of Michigan Engineering made for an innovative atmosphere ready for Pawlowski’s passion.

The Ann Arbor News reported in 1940 on the silver anniversary of Pawlowski’s first aviation course that his “interest in aviation had been fired in 1908 when he witnessed flights by Orville and Wilbur Wright at Le Mans field in France. He enrolled for postgraduate work at the University of Paris when the first chair of aeronautics in the world was established there in 1909.”

It seems the story goes like this: “at that time, the Wright brothers [were in] this little resort town of Pau. . . . Everybody that had any interest in anything modern at the time, kings and queens, royalty from all over, ended up there. . . . All these aviation people were getting their ideas together. The Wright brothers had flown about 16 years before that. And so Orville went to Paris to start selling airplanes . . . and they were part of the elite society—they were the sensation. . . . And at that time, Pawlowski had come down into town and was studying with anybody that he could talk to, and ended up becoming friends with the Wright brothers.”

What was Polish-born Pawlowski doing in France? In May of 1936, the Detroit Free Press reported that in 1908, Pawlowski “was forced by agents of the Czar to flee from his native Poland. ‘Poland was interested in gaining its freedom during the uprising against the Czar in 1905,’ Prof. Pawlowski explains. ‘The Czar set out to make a cleanup in 1908 and in my case it meant that I must run or put in five years in Siberia. I ran. . . . The Wrights were near Paris and that was where I determined to go.’ ”

In addition, Pawlowski told the Free Press that, “ ‘there was a closed valley surrounded by high hills which kept out all breeze . . . ideal for an early day flying field and here the Wrights established the first flying school.’ ” But Pawlowski adds that it was designed for “millionaire sports men and far beyond my means.’ ” So despite his friendship with the Wright family, he went the route of self-education.

He told the Free Press that, “ ‘In those days, you learned by flying,’ he smiles in memory. ‘We would run along the ground and sometimes our speed would lift us in the air. We would measure in the sand the spot where the wheels left the ground and the point where we landed to determine the length of our flights.’ ”

Department lore says, “he didn’t have a full airplane; he had a fuselage with a motor in it. And he would run up and down the runway. This is how he did a lot of his studies. And he would get to the end of the runway, and he would jump out, hit the tail and he would push it around and jump back in. . . . he was just learning aerodynamics.”

The Free Press reported that “sideslips sent his airplane into crashes with such frequency that his savings melted away in hospital and repair bills. Broke and discouraged, he determined to try anew in this country.”

And so Felix Pawlowski left on a journey that made a final, key stop at the University of Michigan’s engineering program. He came to America in 1911 and made his way from sleeping on the benches of New York city to working for companies like General Motors in automobile aerodynamics. But he wanted to get back to the physics of flight and began writing to universities, asking them to consider courses in aeronautical engineering, which of course, he could teach. Seventeen universities turned him down, but Dean Mortimer E. Cooley of the University of Michigan Department of Engineering knew the future when he heard it.

In most of the universities, Pawlowski had been “scoffed at for his belief that [the] manufacture of airplanes would soon boom into a major industry,” wrote the Ann Arbor News in 1940, and said they didn’t have the money in their budgets. But while Dean Cooley said that U-M also didn’t have the money to get an aeronautics course off the ground just yet, he asked Pawlowski to come to the university and teach mechanical engineering until the wind was right and the money was there for a course in aeronautics. In 1914 Cooley put the course in the books and established the department of Aerospace Engineering. On February 5, 1915, Pawlowski walked into a class devoted to flight. He had an annual salary of $800.

Meanwhile, he’d funneled his passion into the Aero Club and students were waiting and ready to get the first undergraduate degree in aeronautical engineering in the country, awarded in 1916. Pawlowski cut a fascinating character on campus with his European dress and was beloved by students, who nicknamed him Pavi. His career spanned decades, involved working for the army during World War I, and in 1930, he was appointed Guggenheim professor of aeronautical engineering. In addition to his inspiring teaching and aeronautical research, he contributed to a greater understanding of automobile wind resistance.

When Pawlowski retired from his U-M post, he returned to live in the town of Pau, France, the site of that exciting time of aviation enthusiasts sharing ideas, risks, bruises, and thrills. And he left Michigan with one of the strongest aeronautics programs in the country, where his excitement and innovation is still very much alive.

“Michigan Aerospace has made so many contributions to shaping the Aerospace landscape as we now know it, that it would be impossible to name all the great accomplishments over the past 108 years of its existence” – says Tony Waas, the present Richard A. Auhll Department Chair. Waas was attracted to join Michigan in 1988 because of its strong legacy in Aerospace. Over the years, Michigan’s Aerospace Alums have included household names like Clarence “Kelly” Johnson (SR71), Harry Hilaker (F16), Bob Furhman (Polaris and Poseidon), Willis Hawkins (Lockheed Constellation), and George Skurla to name a few. The Apollo 15 mission crew was an All-Michigan team. Several recent Aerospace graduates are leaders in the Aerospace field now and continue to innovate and lead the nation in a variety of Aerospace related activities. “I consider UM Aerospace to be a leader in many contemporary megatrends that are shaping the future of our field” quipped Waas.

As Waterhouse says about the work of the Wright brothers and Pawlowski, “we see these historical artifacts and think of the past, but the incredible innovation happening then is still happening here today . . . it’s that Michigan thread.”

For now, the Michigan thread symbolized by the framed artifacts is getting the archival treatment it deserves and is hung in a prominent place in the Francois Xavier Bagnoud (FXB) building, home of the Aerospace department. Chartier misses its presence, of course: “how cool is it to have a piece of the Wright Brothers history sitting in your office? But it’s the right thing to do.” Meanwhile, odds and ends still find their way to his office, some more important than others.

Pawlowski had the fortitude to write those letters to universities across the country, and Dean Cooley had the foresight to clear a space for Pawlowski and his ideas. The Atrium of the FXB building pays tribute to many historical artifacts connected to U-M Aerospace History and also celebrates the accomplishments of notable alumni. What might fill the new blank spaces on the building walls? It’s hard to say, but it won’t stay blank for long, says Waterhouse.

Thanks to the Bentley Historical Library staff for suggesting and collecting such helpful resources.